Patient Stories

Share this page

Every year, thousands of Dana-Farber cancer patients pass through the Institute's doors with inspiring stories of struggle, strength, perseverance, and hope. Here are just a few of those stories.

About Our Patient Stories: Dana-Farber shares patient stories which may include descriptions of actual medical results. Dana-Farber provides personalized care for each patient based on their unique needs; their experiences and results will vary.

From 2013, when I was diagnosed with multiple myeloma as a 22-year-old college senior, until 2016, I felt isolated and insecure. Getting diagnosed with something so rare at 22 was terrifying and overwhelming. As a young person, I hadn’t faced such a struggle before and I didn’t know how to cope.

It all started back in August of 2013. During a dental procedure, it was discovered that my blood pressure was stroke-level high. My dentist, concerned for my well-being, halted the procedure and insisted that I see a doctor to have it checked out.

John Cain reflects on his colorectal cancer journey, "It was a blessing for me to have had that second opinion and to have had the opportunity to meet some wonderful people at Dana-Farber. It was like a family."

After two cancer diagnoses, Kayla Brown got a third chance at life, so she doesn’t take it for granted. "Every single day I am just happy to be here."

After her diagnosis of colon cancer, Christina Crespi knew where she wanted to be treated. As a successful nurse familiar with the health care landscape, Christina immediately sought a specialist in Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s Colon and Rectal Cancer Center.

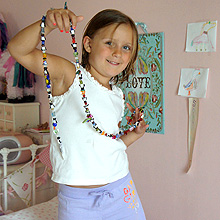

To help Sophie Pettengill adjust to treatment, she was paired with Deborah Berk, MSW, LICSW, a social worker in the Division of Pediatric Psychosocial Oncology, who supported Sophie by accompanying her to procedures, reading to her, and identifying helpful distractions.

Following appointments at another medical institution in Boston, Lynch syndrome patient Susan Ryan described herself as “scared, isolated, and alone.” Then, she found Matthew Yurgelun, MD.

Diagnosed with Hodgkin Lymphoma at age 22, Arieana Carcieri was facing the stark reality that her treatment could affect her fertility. She turned to fertility specialist Sara Barton, MD, for guidance.

Months after receiving a stem cell transplant to cure his severe aplastic anemia, 13-year-old Behaylu Barry returns to the soccer field.

At age 24, Black Hawk pilot Ben Groen was diagnosed with T cell lymphoblastic non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Says Groen, it was "a huge shock." This rare, aggressive cancer was an enemy without a face, but Groen was well trained for combat and employed his army training to fight his cancer as he would any other enemy.

From a registry of seven million donors, Annette was a perfect match for Bob. And three years after the transplant that cured Bob's advanced myelodysplasic syndrome, he met the woman whose stem cells saved his life.

Before a diagnosis of breast cancer, a double mastectomy, and months of grueling treatment, fifth-grader teacher and mom Colleen Sullivan “never, ever” would have described herself as strong But Colleen’s journey fighting cancer at Dana-Farber has given her a new perspective of herself—and on life.

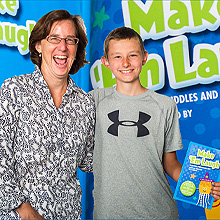

Diagnosed with bone cancer at the age of 11, Jack Robinson tackled treatment if not with a smile on his face, then with a joke on his lips… or more accurately, on paper. The Massachusetts resident compiled and edited a joke book called, “Make ‘em Laugh” to help himself, and other kids who were sick.

By seeking second opinions, participating in clinical trials, exercising, and staying positive, multiple myeloma patient Jim Bond is still enjoying life 20 years after his diagnosis.

Karen Lee Sobol shares her experience and advice as a patient who received treatment for Waldenström's Macroglobulinemia, a slow-growing type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Kelley Tuthill discovered integrative therapies as a way to help her juggle her breast cancer treatment with her roles as journalist, wife, and mother of two children under five.

Diagnosed with cancer in the summer before her junior year, Maria credits the doctors and nurses at the Jimmy Fund Clinic with not only helping her beat cancer but helping her live the life of a normal teen in the process.

When Michael Selsman came home from his morning jog, he noticed a lump on his chest. It was strange, because he'd never seen it before, but he figured it was probably just an irritation. A couple of weeks passed, and the lump grew larger.

High-school student Molly Callahan and Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center nurse Lindsay Roache, RN, have a few things in common: They’ve survived cancer, and they’re committed to helping others.

Rebecca Byrne had waited years for a doctor to tell her: "You are pregnant." She never imagined that just a few months later, she would hear: "You have cancer."

The strings of colorful beads that line Sophie's bedroom represent milestones in her care at Dana-Farber/Boston Children's Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, where she was treated as a toddler for acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Diagnosed with breast cancer during her tour in Iraq, Stacey Carroll never envisioned the type of strength she would need to take on this personal battle.

As a physician who spent years treating blood cancer patients, Steven Weinreb, MD, knows the important role that stem cell transplants play. But he never thought he'd undergo one himself — or experience the side effects.

Cancer, creativity and courage merged at an exhibit of art by patients of Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center.